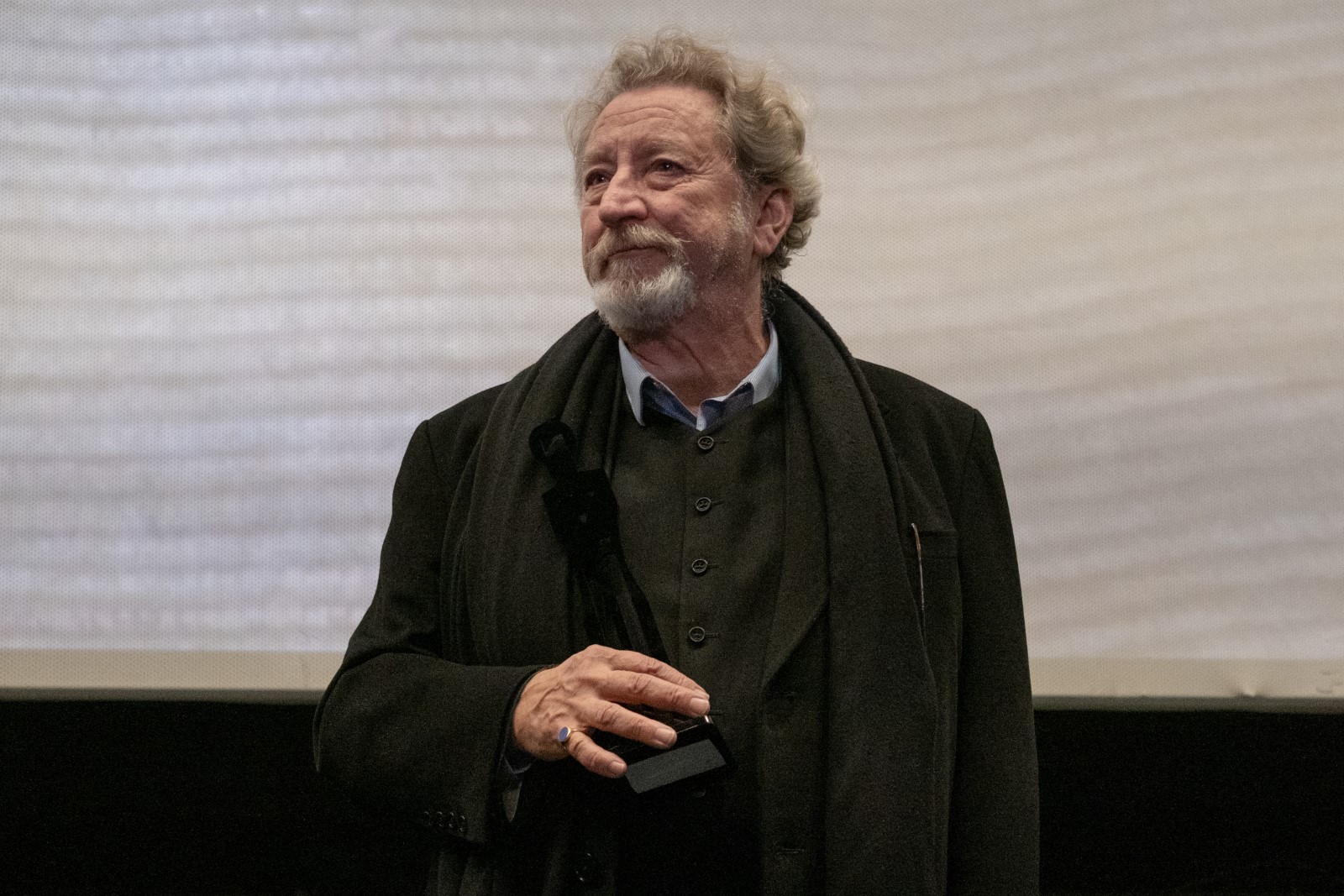

As the son of an immigrant, Robert Guédiguian, a native of Marseille and a director, never succumbed to the idea that the future was without alternatives; he always took a stand on the side of the defeated without surrendering. This is why his cinema, while depicting the uncertainties of the present and the ominous specter of the future, consistently advocates a solution: community and its significance, collective action for the common good, and a departure from individualistic living. A Gramscian optimist and a meticulous observer of the working class since the seventies, Robert Guédiguian has been selected by the Laceno d’Oro International Film Festival to receive the 2023 ‘Pier Paolo Pasolini’ Lifetime Achievement Award

‘Con il cuore cosciente’(‘With a conscious heart’) is one of his favorite quotes, from ‘Le ceneri di Gramsci,’ (‘Gramsci’s ashes’) but what remains today of Pasolini?

It’s a very difficult topic; what an interesting start for our conversation. I can explain what legacy Pasolini has left me with: an ethical and moral question. Pasolini’s stance was that of an intellectual who generated a way of acting: it was always based on doubt, inquiry, and never being fixed in one’s own opinions. He moved forward with great freedom but also with doubts about understanding the best way to exist in the world: intellectually and emotionally. Regarding Pasolini’s figure, what I find extremely important is his constant siding with the most fragile, the weakest, the most vulnerable. For this reason, Pasolini embodies what an intellectual should be.

Your cinema has always spoken about those who has been dominated and defeated, even while changing form and subject. Is the power the only constant component?

Actually, the role of power is interesting because I’ve never really filmed it. I never show the face of power but rather of all those who don’t own it, because I believe one must always fight for the weakest. I’m not interested in capturing power; I only did it once in a film depicting the last days of François Mitterrand (Le passeggiate al Campo di Marte, 2005) because I wanted to depict the vulnerabilities and weaknesses of a president, a man who has always had everything and is facing death. That’s what gripped me: the powerlessness of power. Otherwise, in my films, I want to showcase the greatness of the lives that have never been narrated in stories. This certainly has a very Pasolinian aspect. I want to narrate the sacredness of everyone’s life, especially those who are never been considered because giving them a face and a voice can also give the courage to fight and hold their heads high, not feeling crushed by the presumed superiority of the dominators.

Like Victor Hugo’s Les pauvres gens, a poem that inspired the film Le nevi del Kilimangiaro. What influence does French literature have on your films?

Victor Hugo is a national monument in France; at his death, the greatest funerals in our history were held. Les Misérables is the first book that kids read at school, and, as a young adult, I personally learned to read, thanks to it. Hugo has this power and can be quoted in any context because of the richness, humanity, and even lyricism in his literary production that can be applied to everything. He taught me how to read, but above all, there is a strength in popular novels and stories that reaches everyone, a strength that should never be underestimated. He taught me that one can narrate drama while looking skeptically at elitist intellectuals who live in their ivory towers and think that using melodramatic forms is anti-intellectual. I’m not at all one of those filmmakers who aim to create cold works that only three people see and that most of the audience doesn’t know. For me, Victor Hugo represents this power: the ability to approach many profound topics while remaining accessible and understandable to all. In this regard, two reference filmmakers are John Ford and Jean Renoir: they sure know how to make great cinema and speak to everyone.

One should never follow the axiom that connects high intellectualism to boredom because otherwise, you risk not to being understood by anyone.

Since the beginning, you have consistently worked with the same actors, production team, and crew. Is there a political reason behind this, or does it have a theatrical connotation?

Of course, I believe that ‘theatrical troupe’ is the expression that better encapsulates my idea of making films together. A similar term was used in the 15th and 16th centuries when the text performed was written for the hired actors. The playwrights used to compose their dramas basing them on the company they had available. This process deeply influenced the writing, and that’s how theater was made. Collectively. I don’t like the idea of the artist as a solitary creator who builds everything alone. The writing and staging processes should be done together. I’m always a bit distrustful, even suspicious of those films that aim to depict the world but have a main hero, a lead actor. For me, this can’t exist. I like having many characters because we don’t live in isolation. We change and tell the world collectively.

Earlier, we were discussing the elitist world of culture. What director do you currently feel affinity towards?

I definitely appreciate the filmmaking approach of Nanni Moretti, Aki Kaurismäki, Ken Loach, and the Dardenne brothers, because of their way to connect with the audience. It’s like the Fifth International, following Trotsky’s idea. The world has undoubtedly changed, and most intellectuals today are completely detached from their audience: not only do they not know who they’re speaking to, but perhaps they aren’t even interested in the idea of engaging in a dialogue with the people who watch their films. And then I think of Jean-Luc Godard, Pasolini: there was always a dialogue between those who made cinema and the audience. I recall contributions in the Communist Party’s magazine discussing cinema and art; I particularly remember an exchange between a viewer who had seen a Pasolini film and didn’t understand it, and the director’s explanation. There was a different care, a desire for the works to be understandable, and to collect the opinion of the people who went to see the films. In the ’70s, there were communal forms—whether political parties or workers’ unions—that cared about pedagogy and the relationship with the people. Now there’s complete solitude, and everyone lives detached from others. We’ve stopped asking this question: who are we talking to? Who do we really want to engage with today?

Marseille has been depicted by many writers, from Jean-Claude Izzo to Louis Brauquier and Gian Carlo Fusco. What’s your connection with this city?

I love Marseille so much because it isn’t a French city. When Flaubert first arrived at the Old Port, he said, ‘But this is Africa!’ Throughout history, the whole world has met and mixed in Marseille, while Paris has only recently become a blend. It’s probably due to its position by the sea, facing the Mediterranean, and this tradition of exchange with others. There’s a spirit of openness towards others and no fear of differences, such as skin color. I love this contamination, this impurity, a word I truly appreciate. Whenever I hear the call for ‘purity,’ I head in the opposite direction. Fortunately, Marseille has never been that way.

This interview was first published on the Tortuga Magazine website. https://tortugamagazine.net/premio-alla-carriera-laceno-d-oro-2023-robert-guediguian-intervista/

Bianca Fenizia