As a man of the 20th century, Vincenzo Maria Siniscalchi last thought was about the future. Despite his ninety-two years, he maintained an enduring interest in the Constitution, freedom, democracy, and participation, but above all, in the “possibility of constructing a shared set of values for a brighter future”. These were his words before losing consciousness at the ANPI conference in Naples on Monday, February 12th. His passing, reminiscent of an Athenian politician speaking at a public hearing, inevitably evoked memories of Enrico Berlinguer in Padua, as underscored by Antonio Bassolino.

Throughout his public life, Siniscalchi devoted himself to every possible facet: a “trailblazer”, a mentor to younger generations of Neapolitan jurists, a member of the Superior Council of the Judiciary, and a deputy for three terms (first with the Pds and then with the Ds). He contributed significantly to the drafting of legislative proposals in criminal law. In this field, he distinguished himself as a lawyer for his diligence and professionalism in cross-cutting defenses, without assuming the title of “prince of the bar”. His social background and fame did not influence the quality of his defense in the courtroom.

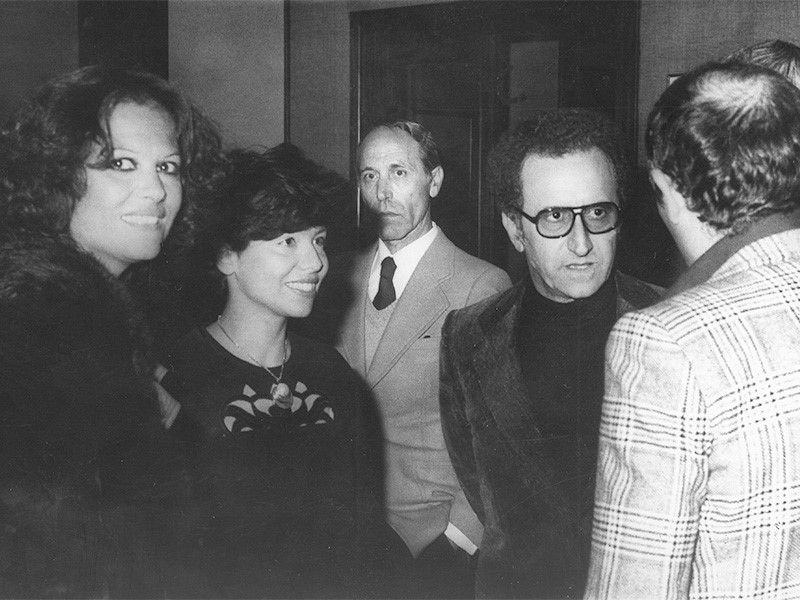

From Diego Armando Maradona to defendants charged with crimes related to the activities of the Armed Proletarian Nuclei (NAP) and Worker Autonomy, and from Franco Califano, Ciriaco De Mita, and Michelangelo Antonioni to unemployed protesters and defendants in the Tangentopoli trials, Siniscalchi’s interventions and publications on freedom of the press and entertainment law are numerous. In his youth, he took time away from his law studies to contribute to the cultural pages of Paese Sera, Il Mattino, and Il Corriere di Napoli.

Film criticism intrigued him, a passion born from his experiences as a spectator at the Circolo del Cinema in Naples, described as a “revolutionary hub of the era” in Michele Vietri’s documentary A chi tanto a chi niente. Here, retrospective works were discovered, as the circulation of French, American, and Soviet cinema had been halted by fascism. Alongside his legal studies, Siniscalchi found the opportunity to explore different perspectives, respect differences, and delve into cinematic arguments. Attending Saturday morning screenings, filling out critical evaluations, and engaging in lengthy discussions until lunchtime, he crossed paths with the future cinema historian Vittorio Martinelli, attended presentations by the Neapolitan mathematician Renato Caccioppoli, and befriended Camillo Marino, ‘a cultural and political agitator’.

“Camillo intrigued me because he told me the stories of the large estates occupations between the fifties and sixties.”

It would only be a short while before Siniscalchi could witness, in the same forgotten lands neglected by industrialization, the birth of the Laceno d’Oro. From its early editions on the Irpinian plateau to its relocation to the city of Avellino in the 1970s, amidst “Camillo Marino’s torment”, the festival faced logistical challenges, however it acquired the character of a cinema festival. These were the years when Domenico Rea, Carlo Lizzani, and Cesare Zavattini served as jury presidents, and the Laceno d’Oro “became a showcase for the most distant cinematographies,’ as Siniscalchi continued in Vietri’s documentary”. A festival that first revealed Yugoslav, Polish, Czechoslovak cinema in Italy, to revive neorealism not as a linguistic structure but as a search for social values within cinematography.

Thanks to its extensive interpretation and openness to all avant-gardes, Tinto Brass’s films “fit in well” in Avellino, as Adelaide De Chiara ironically commented in the reportage La chiave di Tinto (1988) for Epoca. While Brass’s works sparked controversy, scandal, and attempted bans throughout Italy, in the Irpinian capital, La Chiave, Miranda, Salon Kitty, and Capriccio were all premiered and “judged absolutely in line with common decency”, with charges from the national territory being dismissed. An anomaly for a small provincial town, largely Christian Democratic. The journalist quickly unveils the architecture built between the Laceno d’Oro and Tinto Brass, a “strategy from Avellino” involving friends and admirers of the director: Camillo Marino, Giacomo D’Onofrio, Gianni Massaro, a Roman lawyer defending actors and directors, at the forefront of the fight against censorship, and “lawyer Vincenzo Siniscalchi – writes De Chiara – prince of the Neapolitan bar and defender of Brass whenever his films ended up in court”.

This protection went beyond the call of duty, as evidenced by his words for the premiere of Paprika: “Tinto – Siniscalchi reveals to De Chiara – with Paprika achieves his goal fully, which was to revisit sex in a joyful rather than a gloomy way. One cannot imagine how much the controversies of these days hurt, and how much they hurt his wife, the feminists who called Brass a “pig”. Especially since Tinto, and those who know him well, leads a patriarchal life completely within his family circle, very close to his wife and children”.

A chapter in the fight against censorship in Italy that, in its craftsmanship and with the help of “a more tolerant judiciary” – as specified by Paolo Speranza, director of

Quaderni di Cinemasud – which would deserve an in-depth study. And perhaps it could become a film itself, so that it does not just become a thing of the past, but a part of the future. “The value of memory in building a better future”, Vincenzo Siniscalchi would say: this was the theme of the conference he was attending at the ANPI on February 12th at the Plaza del Vomero, discussing democracy. Vincenzo Siniscalchi, a man of the 20th century until the end, defending democracy in a cinema, where he found his end.

Bianca Fenizia